Stablecoins fulfil one simple function within the world of crypto. It helps participants in the crypto universe ground values to the real world without them having to leave it. Imagine a trader, Bob, who wants to buy and sell Bitcoin in order to profit from it. Bob uses money he has made in the real world (USD) to pay for it. Assume, that Bob, like the most of us, ‘on-ramps’ his fiat money into the crypto universe with the help of a centralised exchange - literally the only way to own crypto assets if you’re not a miner and if you don’t have a direct contact sending you Crypto (i.e. P2P) - then, at the moment you want to realize your profits, you’ll have to convert your BTC to fiat somehow. Without Stablecoins, you’ll have to take profits by converting it back to USD, effectively ‘off-ramping’ with every trade. With Stablecoins, however, you could take profits without having to off-ramp into fiat. Skipping this step is crucial for both convenience and cost savings.

Of course, for the average user of Stablecoins, this convenience is truly felt when using decentralized exchanges. In the context of centralized exchanges, stablecoins are less important because users do not experience the difficulties of trading between fiat and crypto because the platform takes care of that for them.

In some ways, stablecoins have one job. To maintain the peg. Maintaining the peg, it turns out, is a really difficult job if you want to achieve capital efficiency at the same time. Ultimately, stablecoin operators are in business because they are for-profit entities that aim to earn interest from the capital they receive from selling minted stablecoins. Having fractionalized reserves is the tried and tested method of gaining a profit.

How then have most Stablecoins faired so far? In this article we’ll closely look at three broad families of stablecoins, classified according to custodial nature as well as risk-absorption properties. At the end of it, we hope to have a good understanding of the major kinds of stablecoins in the market as well as evaluate them as assets. We’ll take a look at custodial stablecoins such as USTC and USDT, exogenously collateralized ones such as DAI, and algorithmic ones such as UST.

Custodial stablecoins

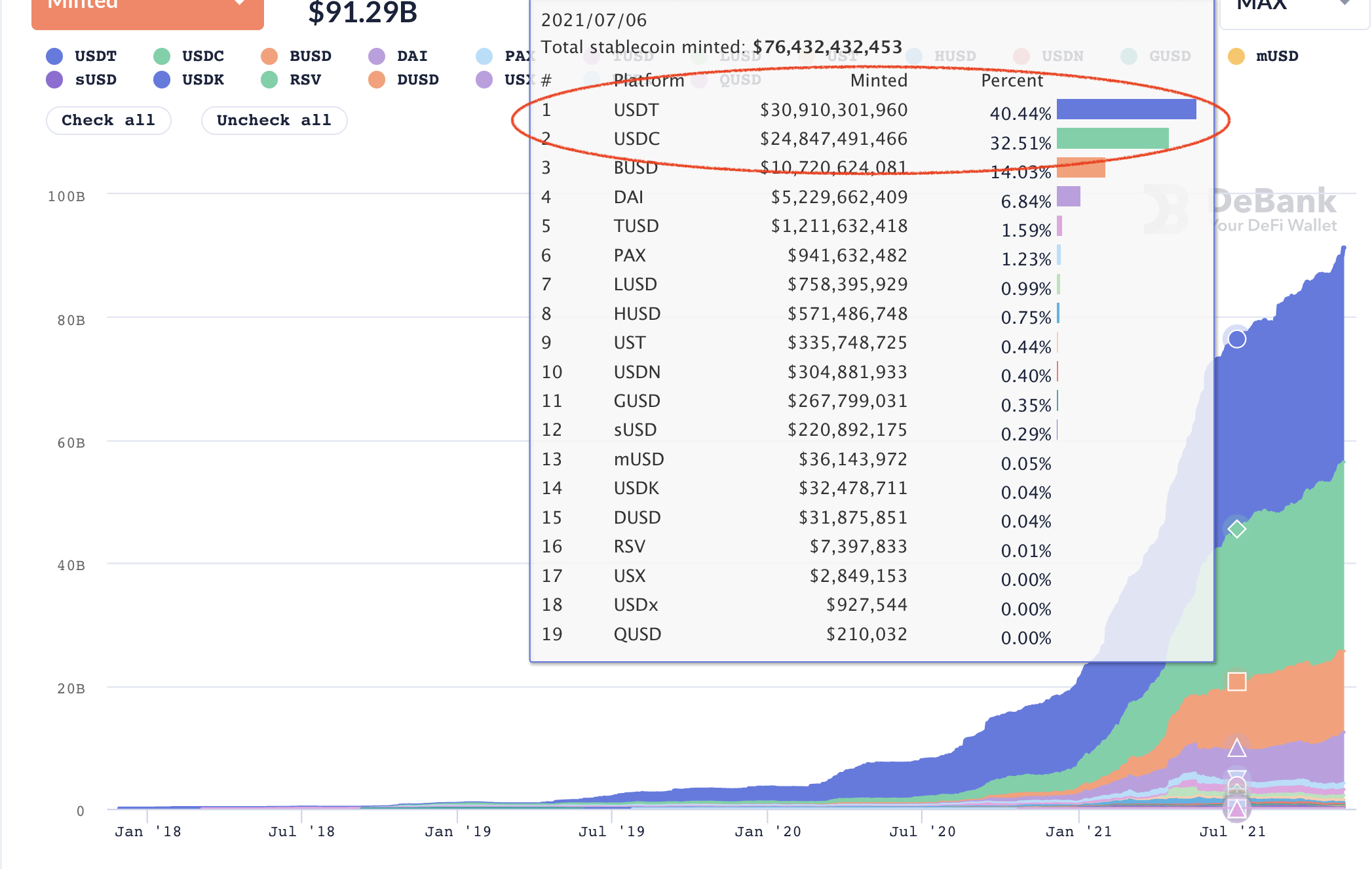

Amongst the older generation of stablecoins, some models have proven to be very resilient. The most popular forms of stablecoins are, in fact, the fully custodial ones, such as USDC and USDT. These stablecoins are collateralized with the asset they’re pegged to (e.g. USD) in a reserve such that it’s always redeemable 1 to 1. Behind the scenes, the actual reserves are smaller in order to capture higher capital efficiency for the stablecoin companies - a common practice known as fractional reserve banking. Stablecoins within this category have consistently taken up between 70% to 80% of total circulating supply since the start of 2018. As of 9th Nov, USDC, USDT and BUSD take up a total of 86.63%, and don’t see any signs of waning.

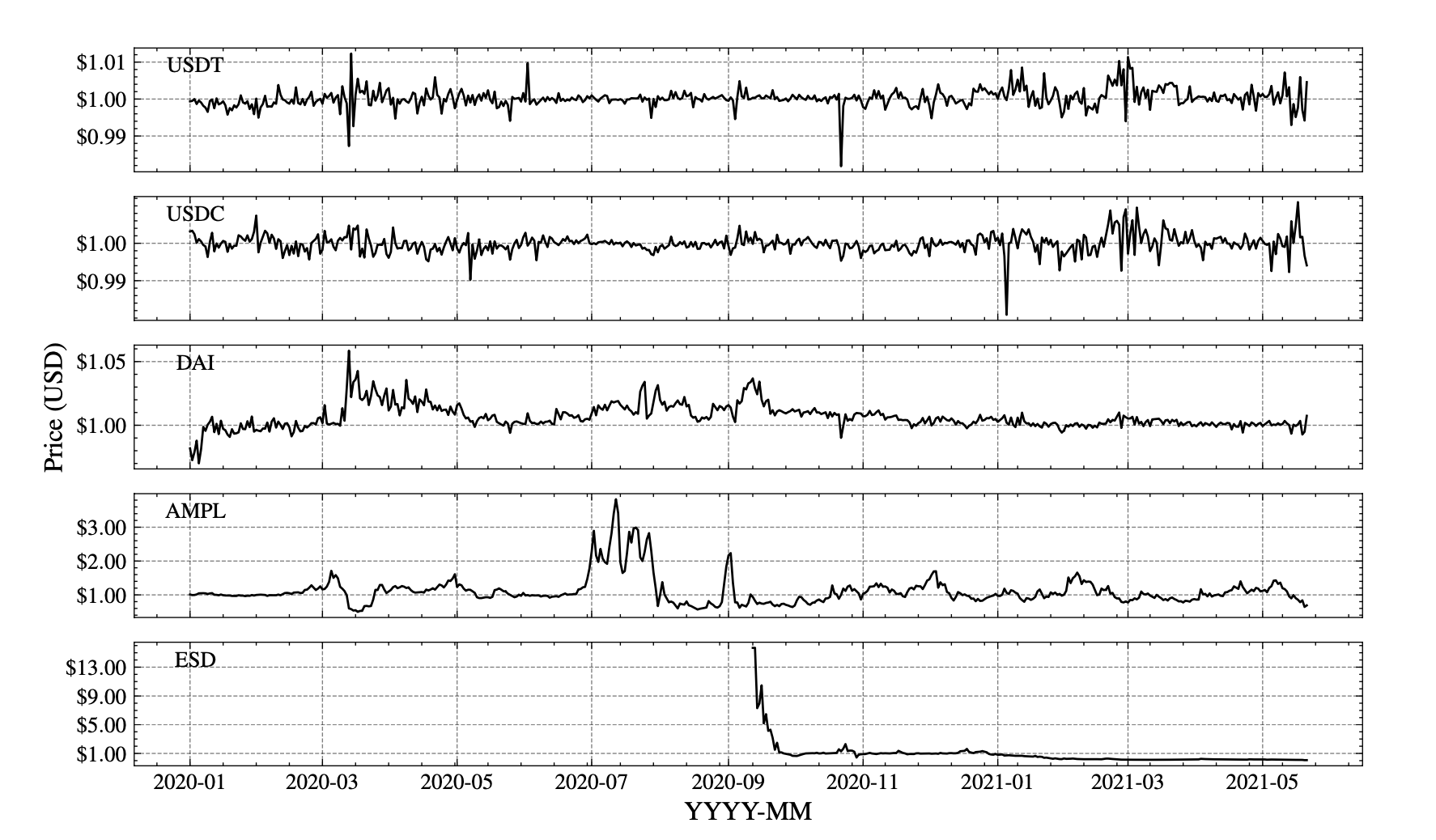

In general, these fiat-backed stablecoins are popular because they have kept the peg pretty well. The average investor finds them easy to understand and interpret. Concepts such as one-to-one backing or one-to-one redeemability (which USDC, USDT and BUSD have all historically employed), convey a straightforward model that the average investor finds familiar and hence trustworthy. From the figure below, we can see that USDT and USDC have both maintained the peg pretty well.

These does not mean there are no risks involved in them. USDT, for instance, has been said to be a ticking time bomb. Given the sheer magnitude of USDT’s market share, the risks here cannot be underestimated. In general, however, fiat-backed stablecoins have generally proven to be resilient thus far.

Classification Schema for Stablecoins

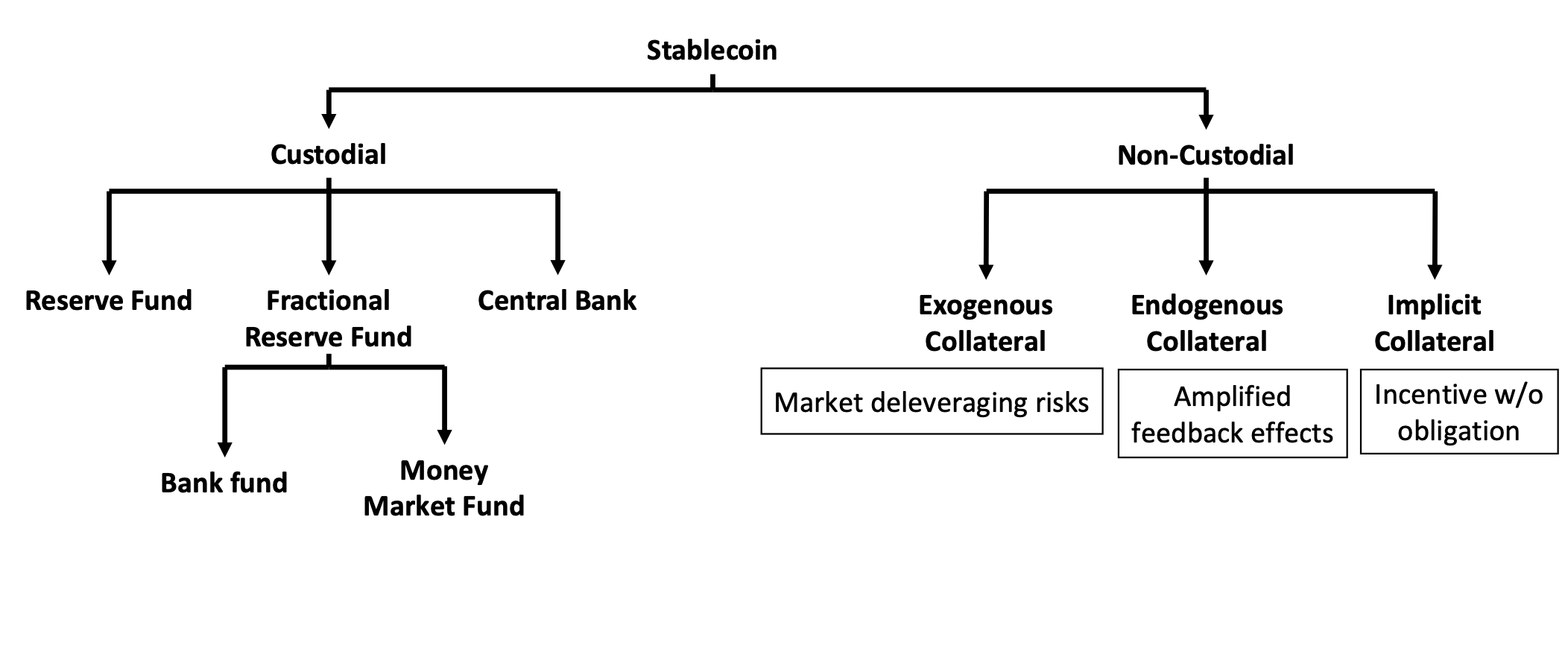

Now, it’s important to introduce some classification schema for thinking about different properties of Stablecoins. The fiat-backed stablecoins we mentioned above belong to the custodial family of stablecoins. They’re custodial because it requires that we trust the third party organization that controls the stablecoin smart contract. Risks of this class include counterparty risk (do they have the reserves they say they have?), censorship risk, and traditional financial risks. On the other hand, we have non-custodial stablecoins. These are stablecoins, such as DAI, where trust in the organization is replaced by economic mechanisms within the smart contract. Within the non-custodial category, we can break the stablecoins up according to the type of collateral - an aspect that would closely affect the type of risks inherent in the stablecoin. First, there are those like DAI, where the collateral is based on ETH (and others). For these we call them exogenously collateralized. Stablecoins such as sUSD (Synthetix) and UST (Terra) are endogenously collateralized - meaning that they’re backed by their own native token. I’ll explain the meaning of ‘backed’ further in the case of Terra. A final category of stablecoins under the non-custodial (or some term algorithmic) family has no collateral backing at all. Such tokens include: ESD, AMPL, BAC. Each type of collateralization structure carries with it its own source of risk.

Exogenously collateralized

Within the exogenously collateralized family of stablecoins, DAI has withstood the test of time and is considered the most successful. Not only has it managed to keep its peg through the years, it’s managed to do so without fiat collateralization. DAI uses the over-collateralization model, by requiring the minting of 1 DAI to be backed by 150% of its equivalent value in Eth. For instance, to open a DAI ETH-A Vault to get 10000 DAI (note: 10000 is the minimum), you’ll need to deposit $15,000 equivalent in value in Eth. This is also called opening a Collateralized Debt Position (CDP). Assuming Eth price is 4500, a deposit of 15000/4500= 3.33 ETH would be able to generate 10000 DAI for you.

Now, the beauty of this system is that you, as the DAI minter, is fully in control of the overall supply of DAI. The protocol takes a hands off approach and does not intervene in controlling the demand and supply of ETH directly. As such, this system is fully decentralized. How much DAI exists in the world depends on how much ETH is locked up in the vaults. On the other hand, the key aspect of this system is that you, as the vault owner and minter of DAI, also take up the majority of risks. The DAI system mandates that once the value of the underlying collateral falls below the liquidation threshold of 150%, your collateral would be automatically liquidated. The specific mechanics is as follows: once the value drops below the liquidation threshold, an auction is called and your collateral (ETH) is sold off to liquidators at a discount. There will also be a 13% penalty charged to you. After the sales, only about 50% of the value of your collateral would go back to you.

Risks

As you can see, with the MakerDAO system, risk is almost solely born by DAI minters. During times of contraction, vault owners invariably lose out. That is one major drawback of such a system design. The other drawback is that having 150% collateralization is not capital efficient. At any point in time, the system holds 150% of its market cap in its reserves: i.e. as idle capital. This is even 50% less efficient than the 1-to-1 backing of the likes of USDC. The tradeoff, of course, comes in the form of resistence to shocks and the ability to maintain the peg - which are of course the core purpose of stablecoins.

Now, I mentioned above that you could only use ETH as collateral to mint DAI. That is now not accurate. For a long time during the intial conception of DAI, that was indeed the case. However, the protocol has changed its policy and now you could use a much wider range of collateral, including the likes of wBTC, renBTC, YFI, UNI, MATIC, and USDC. The comprehensive list can be found here.

DAI Peg Maintenance Strategy

It is also extremely important for us to understand how DAI maintains its peg. The short answer to this is: the protocol engages in three core strategies to respond to increases and decreases in demand to keep the peg at $1. Its first line of defence is in the stability fees. Stability fees are basically the fees, or interest rate, you pay to open the vault. They vary between 1% to 8%. For instance, at the time of writing, the Eth A vault has stability fees of 2.5% whilst Eth B vault has stability fees of 8%. This means that when you open an Eth A vault of 10,000 DAI, you’ll pay 2.5% of 10,000 (250DAI) annually to maintain this position. Like all things Defi, the stability fee is a variable one that’ll adjust according to demand and supply of DAI.

The stability fee functions a little like central bank interest rates. When demand is high (price of DAI > $1.0), stability fees would be adjusted downwards. This has the effect of incentiving vault ownership and opening, hence boosting the supply of DAI. As the supply rises, price of DAI falls. Vice versa, during times of contraction (low demand for DAI), the price of DAI would drop below the peg (< $1.0). Stability fees are increased, disincentivizing vault ownership. Vaults are closed, and DAI is burnt. The supply of DAI falls, resulting in increase in price of DAI. Stability fees hence, as their name suggests, function as levers for controlling DAI supply.

Now, this system is not perfect. It has been observed in this brilliant post that there are upper limits to how much DAI supply can be boosted, resulting in the observation that it does not scale. What does this mean? It means that when price of DAI > $1.0, the demand for buying DAI is very low as the buyer expects price to normalize again. The same function that keeps DAI stable also curtains demand. As the authors of the article brilliantly observed, ‘the important part for stability is getting the price of your coin up to $1. But the important part for scalability is getting the price back down to $1.’ Now, an astute reader will wonder: does it matter if DAI doesn’t scale, or reach the level of USDC or USDT? What does stablecoin scalability even mean? That’s a topic reserved for another article — but I’ll leave this question here for now.

The second way DAI maintains its peg is with the DAI savings rate (DSR). Introduced in November 2019, the DSR can be imagined as a DAI deposit account (essentially a smart contract) that provides interest on DAI ‘staked’. During times when we need to push the peg up (DAI < $1.0), DSR is increased by the protocol, making it more attractive to stake DAI. An attractive DSR will increase the demand for buying DAI at an exchange, and depositing the Dai in the DSR contract to earn interest. During times where DAI needs to be pushed downwards, the protocol will reduce the DSR, disincentivizing demand. Therefore, whilst stability fee can be thought of as a supply-side lever, DSR is a demand side lever.

The final way in which the peg is maintained is via the peg stability module. This module is a relatively new feature that was born out of the inability of the protocol to maintain the peg using its first two lines of defence, as seen during the Black Thursday event. Introduced as a response to Black Thursday by the protocol and after rounds of community discussions, the peg stability module was implemented in MIP29 in Nov 2020. The core idea behind the peg stability module is that it allows users to swap other stablecoins for DAI at a fixed rate to keep DAI pegged to $1. For instance, the USDC-backed PSM allows a user to swap 1 USDC for 1 DAI. This helps keep DAI peg close to $1 when DAI demand outstrips supply. Decentralization Maxis will argue that this is a ‘cheat’, and indeed, this does mean that DAI is somewhat ‘backed’ by centralized assets, introducing another class of risks.

So, in essence, DAI maintains its peg through a combination of the above approaches. On the supply side, it manipulates the stability fees. On the demand side, it alters the DSR. Then, to further bolster the system, it allows users to swap stablecoins for DAI via its PSM. This effectively also allows arbitrageurs to play a greater role in stabilizing the price of DAI, and in some ways mitigating DAI’s scalability problem as mentioned above. So far, this system has worked out well enough. During extreme market events such as the May crypto selloff, which should technically increase the demand for DAI, the price of DAI has held pretty close to the peg.

As such, we can see that after many cycles of iteration from its core dev team, DAI seems to be in quite a robust state. Despite weaknesses such as overburdening DAI vault owners with liquidation risks and low capital efficiency, it does its main job of maintaining the peg fairly well. Of course, DAI’s true levels of resilience could only be seen during the next stress test - another Black Thursday like event where the price of the underlying collaterals fall drastically within hours.

Algorithmic stablecoins

We have explored exogenously collateralized models of stablecoins such as DAI in quite great detail, because it’s important to understand the mechanics of what holds its peg up. There is another category of extremely innovative and as-of-now successful model of stablecoin that does not depend on an external collateral at all. That is, the seignorage shares model of stablecoin such as Terra’s UST. In an environment where many ‘algorithmic’ stablecoins have long since depegged, the fact of Terra’s resilience testifies to the possibility that real life working algorithmic stablecoins might in fact be converging towards seignorage shares model. Before you move on, it’s recommended that you read this article on how the two main families of stablecoins work - the rebase model and the seignorage shares model.

Just to provide a brief background of these two models. Recall that all stablecoin pegging issues boil down to the ability of the protocol to alter the supply and demand of the coin to counter-act the effects of the depeg. Whilst non-algorithmic solutions like DAI relies on a system of incentives, ‘algorithmic’ models such as the rebase model used by Ampleforth goes straight to the source itself, by altering the total supplied amount directly. How? Now, imagine the supply of tokens is an integer controlled by the protocol. Unlike DAI, where the supply could only increase via minting of a collateral, the rebase model literally alters this supply integer so that, when you take the demand divided by this new supply, the value of AMPL token is $1USD. What about the dilution of token holder value, you might ask. The answer to that is that every individual wallet that holds AMPL will have the amounts changed at every rebase. For instance, if supply is increased by 10% at one rebase cycle, a user holding 1000 AMPL will now hold 1100 AMPL tokens, and a holder who holds 1 AMPL token will hold 1.1 AMPL token. The rebalance of supply is done on the individual wallet level, affecting every single stakeholder of the token. During expansion, holders have more AMPL tokens. During contractions, they have less.

Obvious flaws of this system has been pointed out, but so far, nothing summarizes it as succintly as the following quote:

“Price stability is not only about stabilising the unit-of-account, but also stabilising money’s store-of-value. Hayek money (rebase model) is designed to address the former, not the latter. It merely trades a fixed wallet balance with fluctuating coin price for a fixed coin price with fluctuating wallet balance.”

In other words, it kicks the tin down the road - volatility is reflected not in terms of price, but in terms of amounts in my wallets. The seignorage model, on the other hand, comes into play to address this.

In brief, the seignorage model consists of two tokens. A stable token, and a volatile one what absorbs risk on behalf of the stable token. According to Robert Sams, the owners of the latter token (so called ‘seigniorage shares’) are the ‘sole receptors of inflationary rewards from positive supply increases and the sole bearers of the debt burden when demand for the currency falls and the network contracts’. In other words, much like share holders, they take on the risks for the first, stable token.

Terra UST/LUNA

How does that work in reality? We see an instance of that in the Terra/Luna model. Within the Terra ecosystem, UST is the stablecoin, and LUNA is the volatile token. The main mechanism that allows for the risk aborption function of the LUNA token is the existence of an on-chain swap mechanism. Now, the protocol dictates that at any point, users can ‘swap’ their UST for LUNA in the following way: 1 UST can be burnt for $1USD equivalent of Luna to be minted. Let’s work through an example to see how that works.

During times of economic contraction (i.e. demand for UST is low - e.g. UST = $0.97), arbitrageurs will be incentivized to get UST from off-chain markets at a discount. Let’s say they get 1UST for $0.97USD . They then take their 1UST to the on-chain swap mechanism, and swap it for $1USD worth of Luna. Suppose Luna’s price is at $5 - the arb would receive 0.2 amount of LUNA tokens in this way, when with $0.97USD of his initial capital, he could buy only 0.194 amount of LUNA. Through this method, he pocket a 3% risk-free profit.

From the perspective of the protocol, this implies that arbitrageurs help keep the price of UST stable by selling UST (increasing supply) and buying into Luna during times of contraction (UST < $1), and buying UST and selling Luna during times of expansion (UST > $1). UST’s volatility is thus externalized onto Luna.

Risks to the seigniorage model

So far, the system has worked pretty well. However, there are risks involved. For instance, given that much of the volatility and risk is held by LUNA token holders and validators, there is only incentive for them to continue doing so if they believe that the long run value of LUNA will rise. The Terra protocol goes to great extents to reassure them of the short run value. One, to reward LUNA token holders during times of contraction, LUNA validators are allocated bolstered staking rewards resulting from increasing the tax rate on stablecoin transactions on the network. Two, the staking rewards are further boosted by increasing the on-chain swap fees for swaps from UST to LUNA. So, unlike the DAI system of using broad based macro-economic levers such as savings rates and stability fees, Terra chooses to use a swap transaction fees approach to reward holders of risks. To reward validators long term, Terra protocol ensures that the staking rewards continue in a predictable fashion upwards - therefore signaling to the validators that they are being rewarded for taking on short term volatility in the form of long term gains. As the ecosystem grows, Terra’s validators will be increasingly compensated in the form of scarcer LUNA supply.

Of course, all these are yet to be stress-tested so far. The seigniorage model of Terra ultimately works like betting on shares of a company, where shareholders choose to stomach short term volatility in hopes of long run increases in share prices. This is a novel design insofar as stablecoins go. However, the broader question remains: what if the validator class collectively realizes that the long run rewards are not as attractive? In what scenarios would that occur, and what effects would it have on UST peg parity? All these are possible sources of risk.

Conclusion

To conclude, the difference between various strains of stablecoins lie in the various kinds of risks as well as who bears them. Centralized ones such as USDT and USDC suffer primarily from regulatory/legal risks, where the risks of a depeg in USDT, for instance, would be bore by all holders of USDT and the crypto economy at large. Collateralized stablecoins such as DAI push risk onto the shoulders of vault owners (or minters of the stablecoin), such that the risk of a rapid fall in the value of the underlying collateral in market crunch is theirs to bear alone. Within algorithmic designs such as the seigniorage shares system of Terra, risk is born by validators and investors in the long run stability and growth of the system in the form of LUNA ‘shares’ ownership. UST is kept stable as long as the validator class believes in the long term growth of the Terra network. The price of short term volatility in UST is absorbed by LUNA holders in the form of value dilution. As long as they believe that value will rise back up again, they’ll continue to hold LUNA instead of burning it for UST.